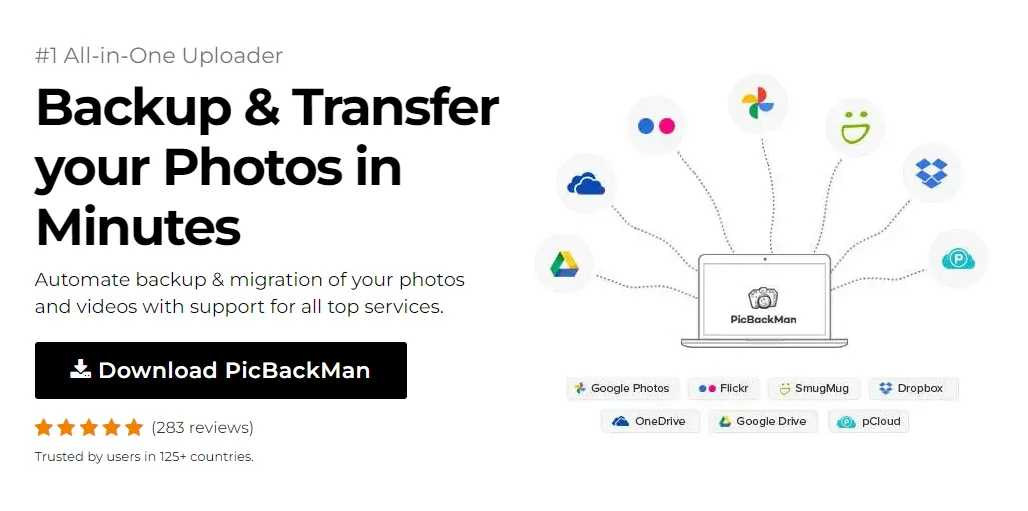

Why is it the #1 bulk uploader?

- Insanely fast!

- Maintains folder structure.

- 100% automated upload.

- Supports RAW files.

- Privacy default.

How can you get started?

Download PicBackMan and start free, then upgrade to annual or lifetime plan as per your needs. Join 100,000+ users who trust PicBackMan for keeping their precious memories safe in multiple online accounts.

“Your pictures are scattered. PicBackMan helps you bring order to your digital memories.”

How does small aperture help you control light?

Light control is the essence of photography, and understanding how to manage it can transform your images from ordinary to extraordinary. One of the most powerful tools photographers have for controlling light is aperture - specifically, using a small aperture. In this comprehensive guide, we'll explore how small apertures help you control light and how you can use this knowledge to create stunning photographs.

What Is Aperture in Photography?

Before diving into the benefits of small apertures, let's clarify what aperture actually is. The aperture is the opening in your lens through which light passes to reach your camera's sensor. It's measured in f-stops (like f/16 or f/22), and here's the key thing to remember: the higher the f-number, the smaller the aperture opening.

Think of aperture like the pupil in your eye. When it's bright outside, your pupil gets smaller to limit light entry. When it's dark, your pupil expands to let in more light. Your camera's aperture works in exactly the same way.

Understanding F-Stops and Aperture Size

The f-stop scale can be confusing at first because it seems backward. Common f-stops include:

- f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8 (Large apertures = more light)

- f/4, f/5.6, f/8 (Medium apertures)

- f/11, f/16, f/22, f/32 (Small apertures = less light)

Each step down the scale (moving from f/2.8 to f/4, for example) reduces the amount of light entering by half. This relationship between aperture size and light is crucial to understanding light control.

How Small Apertures Control Light

Small apertures (high f-numbers like f/16 or f/22) help you control light in several important ways:

1. Reducing Light Intensity

The most direct way small apertures control light is by reducing the amount that reaches your sensor. This is particularly useful in bright conditions where too much light might overexpose your image. By choosing a small aperture, you can shoot in bright sunlight without blowing out the highlights in your photo.

2. Increasing Depth of Field

Small apertures dramatically increase depth of field - the zone of acceptable sharpness in your image. When you use f/16 instead of f/2.8, much more of your scene will be in focus, from foreground to background. This is ideal for landscape photography where you typically want everything from nearby rocks to distant mountains to appear sharp.

3. Creating Sunstars and Light Rays

When you photograph a bright light source (like the sun) with a small aperture, the light diffracts around the aperture blades, creating a starburst effect. These "sunstars" can add a magical quality to landscape and architectural photos. The smaller your aperture, the more pronounced this effect becomes.

4. Extending Exposure Time

By restricting light, small apertures require longer shutter speeds to achieve proper exposure. This can be used creatively to blur moving elements like water or clouds while keeping stationary objects sharp.

Practical Applications of Small Apertures

Understanding the theory is one thing, but seeing how small apertures apply to real photography situations makes the concept clearer:

Landscape Photography

Landscape photographers regularly use small apertures (f/11 to f/16) to ensure both foreground and background elements are sharp. The increased depth of field means that beautiful rock formations in the foreground and distant mountains can all be in focus simultaneously.

Small apertures also help create those beautiful sunstar effects when the sun is visible in the frame, adding an eye-catching element to sunrise and sunset shots.

Architectural Photography

When photographing buildings, small apertures help ensure that details from the nearest column to the farthest corner are all sharp. This is especially important for interior architectural photography, where you want to capture the entire room in focus.

Macro Photography

Macro photography naturally has an extremely shallow depth of field. Using a small aperture helps extend that depth of field so more of your tiny subject is in focus. This is crucial when photographing insects, flowers, or other small objects where every detail matters.

Bright Light Conditions

When shooting in bright sunlight, small apertures help prevent overexposure. This is particularly useful on sunny beach days or in snow, where reflective surfaces amplify light intensity.

The Exposure Triangle: Balancing Aperture with ISO and Shutter Speed

Aperture doesn't work in isolation. It's part of the exposure triangle, along with ISO and shutter speed. When you choose a small aperture, you're reducing light, which means you'll need to compensate with either:

- A slower shutter speed (allowing more time for light to reach the sensor)

- A higher ISO (increasing the sensor's sensitivity to light)

- Or some combination of both

This balancing act is at the heart of exposure control in photography. Let's look at how these elements work together:

| Situation | Aperture | Shutter Speed | ISO | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bright daylight landscape | f/16 (small) | 1/125 sec | 100 | Sharp throughout, well-exposed |

| Waterfall in daylight | f/16 (small) | 1/15 sec | 100 | Sharp scene, silky water |

| Indoor architecture | f/11 (small) | 1/15 sec | 800 | Sharp throughout, adequate exposure |

| Macro flower | f/16 (small) | 1/60 sec | 400 | Maximum detail in flower |

Challenges and Limitations of Small Apertures

While small apertures offer tremendous benefits for light control, they do come with certain challenges:

Diffraction

Diffraction is a physical property of light that causes a slight softening of image quality when light waves bend around the edges of a very small aperture. Most lenses start to show diffraction around f/16, becoming more noticeable at f/22 and beyond. This means that while you gain depth of field with smaller apertures, you might sacrifice a bit of overall sharpness.

Longer Exposure Times

Smaller apertures require longer shutter speeds, which can introduce camera shake if you're not using a tripod. This is why a sturdy tripod is essential gear for landscape photographers who regularly use small apertures.

Limited Low-Light Performance

In low-light conditions, small apertures may require impractically long exposures or very high ISOs, potentially introducing noise into your images.

Finding the Sweet Spot: Optimal Aperture Settings

Every lens has what photographers call a “sweet spot” - the aperture at which it delivers its sharpest results. This is typically 2-3 stops down from the widest aperture. For example:

- For an f/2.8 lens, the sweet spot might be around f/5.6 to f/8

- For an f/4 lens, the sweet spot might be around f/8 to f/11

When maximum sharpness is more important than extreme depth of field, consider using your lens's sweet spot rather than its smallest aperture.

Step-by-Step Guide to Using Small Apertures Effectively

Let's put all this knowledge into practice with a step-by-step approach to using small apertures:

Step 1: Assess Your Scene and Light Conditions

Before deciding on aperture, evaluate what you're photographing and the available light. Are you shooting a landscape where you want everything in focus? Is it a bright sunny day? These factors will influence your aperture choice.

Step 2: Set Up Your Camera

Switch to Aperture Priority mode (A or Av on most cameras) or Manual mode (M) to have direct control over your aperture settings.

Step 3: Choose Your Aperture

For maximum depth of field, select a small aperture like f/11 or f/16. Remember that going too small (f/22 or beyond) might introduce diffraction, slightly reducing overall sharpness.

Step 4: Stabilize Your Camera

Since small apertures often require slower shutter speeds, use a tripod to prevent camera shake. If a tripod isn't available, find another way to stabilize your camera or increase your ISO to allow for faster shutter speeds.

Step 5: Focus Carefully

When using small apertures for landscapes, focus about one-third of the way into the scene to maximize depth of field (this is known as the hyperfocal distance technique).

Step 6: Check Your Exposure

Review your image and histogram to ensure proper exposure. Adjust your ISO or shutter speed as needed while maintaining your chosen aperture.

Step 7: Fine-Tune Based on Results

If your image lacks sharpness due to diffraction, try opening up your aperture slightly. If parts of your image are still out of focus, consider focus stacking techniques for extreme depth of field without diffraction.

Advanced Techniques with Small Apertures

Once you've mastered the basics, try these advanced techniques that leverage small apertures:

Long Exposure Photography

Smaller apertures naturally lead to longer exposures, which can be used creatively to blur moving elements like water, clouds, or people. In bright conditions, you might need to add a neutral density (ND) filter to achieve very long exposures even with small apertures.

Focus Stacking

To overcome diffraction limitations while still getting extreme depth of field, try focus stacking. This involves taking multiple photos at different focus points (using a moderate aperture like f/8) and then combining them in post-processing for maximum sharpness throughout.

HDR with Small Apertures

High Dynamic Range (HDR) photography pairs naturally with small apertures. Both techniques help manage challenging lighting conditions - small apertures control the amount of light, while HDR techniques help capture detail in both highlights and shadows.

Small Aperture vs. Large Aperture: A Comparison

To fully appreciate how small apertures help control light, let's compare them directly with large apertures:

| Feature | Small Aperture (f/16, f/22) | Large Aperture (f/1.4, f/2.8) |

|---|---|---|

| Light transmission | Restricts light | Allows more light |

| Depth of field | Deep (more in focus) | Shallow (less in focus) |

| Best uses | Landscapes, architecture, macro details | Portraits, low light, background blur |

| Shutter speed impact | Requires slower shutter speeds | Allows faster shutter speeds |

| Light source effect | Creates sunstars/starbursts | Produces smoother light points |

| Diffraction | More likely at smaller apertures | Not an issue |

Equipment Considerations for Small Aperture Photography

To make the most of small aperture photography, consider these equipment recommendations:

Tripod

A sturdy tripod is essential for small aperture photography, as longer exposure times can lead to camera shake if hand-held.

Remote Shutter Release

Even pressing the shutter button can introduce vibration. A remote release or using your camera's self-timer function helps eliminate this source of blur.

Neutral Density Filters

ND filters reduce light entering the lens, allowing for even longer exposures or the use of small apertures in extremely bright conditions.

Quality Lenses

Better quality lenses typically perform better at small apertures, with less diffraction and better overall sharpness.

Quick Tip to ensure your videos never go missing

Videos are precious memories and all of us never want to lose them to hard disk crashes or missing drives. PicBackMan is the easiest and simplest way to keep your videos safely backed up in one or more online accounts.

Simply download PicBackMan (it's free!) , register your account, connect to your online store and tell PicBackMan where your videos are - PicBackMan does the rest, automatically. It bulk uploads all videos and keeps looking for new ones and uploads those too. You don't have to ever touch it.

Common Mistakes When Using Small Apertures

Avoid these common pitfalls when working with small apertures:

Going Too Small

Using the smallest aperture your lens offers (like f/32) might actually reduce image quality due to diffraction. Often, f/11 or f/16 provides sufficient depth of field with better overall sharpness.

Forgetting About Camera Stability

Smaller apertures mean slower shutter speeds, which demand proper stabilization. Always use a tripod or stable surface when shooting with small apertures.

Ignoring the Wind

When shooting landscapes with small apertures and slow shutter speeds, even a slight wind can blur foliage. In windy conditions, you might need to compromise with a slightly larger aperture to allow faster shutter speeds.

Not Accounting for Subject Movement

The longer exposures required by small apertures mean that any moving subject might blur. This can be used creatively but needs to be planned for.

Real-World Examples of Small Aperture Photography

Let's look at some typical scenarios where small apertures excel:

Grand Canyon Landscape

A photographer capturing the vastness of the Grand Canyon would likely use an aperture of f/16 to ensure both the nearby rock formations and the distant canyon walls are in sharp focus. The small aperture also helps create a sunstar effect if the sun is in the frame, adding visual interest to the image.

Waterfall Photography

When photographing a waterfall, a small aperture like f/16 serves two purposes: it keeps the surrounding rocks and vegetation sharp while the slower shutter speed (necessary due to the small aperture) creates that silky, flowing effect in the water.

City Architecture

Photographing a cityscape with tall buildings requires a small aperture to maintain focus from the nearest structures to the farthest skyscrapers. The small aperture also creates attractive starbursts from street lights and illuminated windows when shooting at dusk.

Macro Flower Photography

When capturing the intricate details of a flower, a small aperture helps extend the naturally shallow depth of field in macro photography, allowing more of the flower's structure to remain in focus.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is considered a "small aperture" in photography?

In photography, apertures with high f-numbers like f/11, f/16, f/22, and f/32 are considered small apertures. These settings create a smaller physical opening in the lens, restricting the amount of light that reaches the camera sensor while increasing depth of field.

Does using a small aperture always guarantee sharper images?

Not. necessarily. While small apertures increase depth of field (making more of your scene appear in focus), extremely small apertures (typically f/22 and beyond) can actually reduce overall image sharpness due to a phenomenon called diffraction. Most lenses perform best at middle apertures like f/8 or f/11.

How can I use a small aperture in bright daylight without overexposing?

In very bright conditions, even a small aperture might let in too much light. You can compensate by using a faster shutter speed (up to your camera's maximum), lowering your ISO to its base setting (typically 100), or adding a neutral density (ND) filter to further reduce light entering the lens.

Why do small apertures create starburst effects around light sources?

Small apertures create starbursts because light diffracts (bends) around the aperture blades in your lens. The smaller the aperture, the more pronounced this effect becomes. The number of points in the starburst typically matches the number of aperture blades in your lens, with even-numbered blade counts usually creating the same number of points and odd-numbered blade counts creating double the number of points.

Can I use small apertures for portrait photography?

While portrait photographers typically prefer larger apertures for background blur, small apertures can be useful in certain portrait situations. Group portraits benefit from small apertures to keep everyone in focus, and environmental portraits where the surroundings are important to the story might use smaller apertures to maintain detail throughout the frame. Just be aware that in lower light, you'll need to compensate with slower shutter speeds or higher ISO settings.

Conclusion

Small apertures are powerful tools for controlling light in photography. They help you manage bright conditions, increase depth of field, create stunning sunstars, and slow down exposure times for creative effects. While they come with challenges like diffraction and the need for camera stabilization, understanding how to use small apertures effectively can dramatically improve your landscape, architectural, and macro photography.

The key is finding the right balance - choosing an aperture small enough to achieve your creative vision without going so small that diffraction reduces overall image quality. With practice and experimentation, you'll develop an intuitive sense of when and how to use small apertures to control light and create compelling images.

Remember that photography is all about balance and trade-offs. Small apertures give you tremendous control over light and depth of field, but they require compromises in other areas like shutter speed and potentially overall sharpness. By understanding these relationships, you'll be better equipped to make informed decisions that help you capture exactly the image you envision.